How can person and job be matched for the perfect date?

It is extremely difficult to match one person with another by using technology to send them on a date. There will be numerous factors and expectations that have to be taken into account. Do they have similar interests? Are they living in the same area? What are their goals? And then there are plenty of hidden expectations regarding things such as appearance. Matching has always been a complex task.

The same is true when it comes to bringing together the right person for the right job. Even for specialists with years of experience, matching jobs and skills is a huge challenge. Who works well with what? How can you be sure of making a good decision? Every day, such questions have to be correctly answered in order to be able to successfully match person to job. This requires thorough knowledge and good information. The expectations of employers and potential employees are high. Can a machine or an algorithm more than satisfy these expectations?

Is good matching possible?

Firstly, let’s determine whether good matching is even possible. Matching is the act of combining complementary attributes of two entities, in our case job and person. However, even in this context the word ‘matching’ can have various meanings. In some jobs, whether a candidate is suitable for a given job is merely a question of whether he or she is able to work. If you are physically healthy, for example, you should be able to pick strawberries. There are other jobs, however, that require a variety of certificates, specializations and experience. Try to match a neonatal surgeon to a job in a hospital department and this becomes clear.

Although HR specialists realize that the tiniest details have to be considered during the matching process, their task remains highly complex. This is because the prevailing conditions are constantly changing. Requirements that were commonplace yesterday no longer apply today, and in turn today’s requirements will no longer be valid tomorrow. How we define job, prospective employee and labor market shifts all the time. Who would have needed a Director of Digital Development a few years ago? And who would have cited such a specialization in his or her CV?

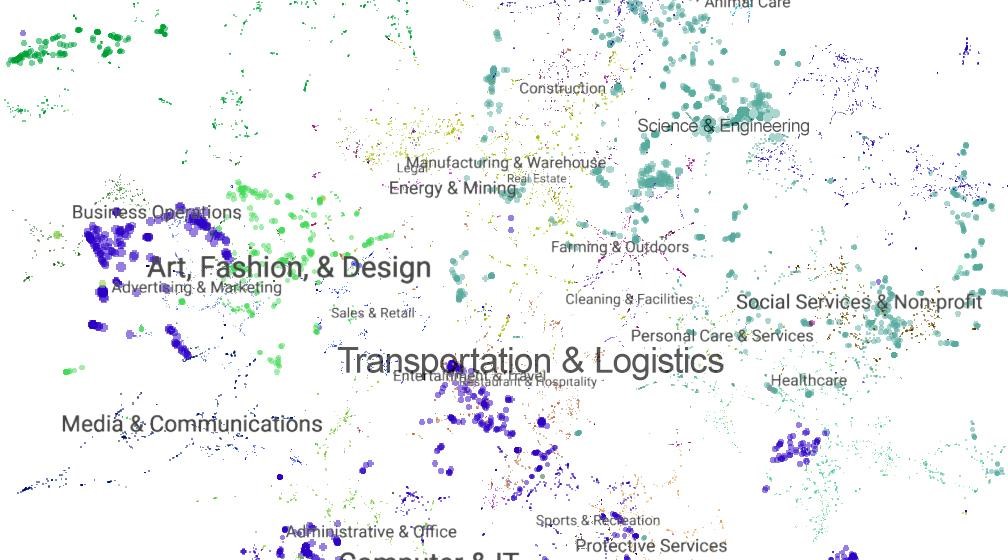

Matching becomes far more complex when a machine has to deal with the task. A machine has to apply all the experience and knowledge of the specialist in the same way, pay attention to the smallest details and react to changes in the labor market. Suppliers of such machines focus on different data in order to overcome this highly complex problem. For example, former job titles of applicants or their skills are taken into account. An algorithm then compares job requests and CVs, and a match is made. Successful?

Bricklayer equals bricklayer. Sales consultant equals sales consultant?

Some algorithms, as we have heard, will make a match based on former job titles. If the candidate had position X at company A, he or she can also hold position X at company B, no? This may have held true in the past, yes. We used to be general practitioners, secretaries, lawyers, bricklayers, etc. Today we are sales consultants, data ninjas, facility managers, etc. Is a sales consultant someone who works in a retail shop and advises customers? Or someone who prepares offers, takes up orders and negotiates contracts with customers? Such questions are already being asked by specialists when they look at CVs. And now machines should be able to make such distinctions efficiently.

Job titles are therefore often too generic. Or too specific, as internal company terms influence job titles and therefore tend to describe functions. Nowadays, everyone is some kind of manager. Without a more detailed description of the jobs we would often be lost and would not know whether an applicant is really suitable for a position – or vice versa.

Comparing skills

A job title is not enough for good matching. So other job matching providers solve the matching problem by using other parameters – they look at skills and competences, since these represent the ‘content’ behind descriptions of sometimes cryptic job titles. Skills-based or competence-based matching is more meaningful and promising because it takes into account not only a title previously held by an applicant, but also that person’s knowledge, talents, insights and education. Thus, one considers the candidate’s skills and the skills required for a job, and matches them.

This sounds logical: I want a manager who is open-minded, communicative, strong in leadership and good at solving problems. I find someone who outlines such qualities in his/her résumé and thus corresponds to my criteria. So, are skills now a reliable factor for machines to evaluate the perfect match for my vacancy?

Let’s take a closer look at skills. Skills result from knowledge. Aristotle said that knowledge is the absolute truth. Absolute truth can only be attained if one has experienced and tested the knowledge oneself. Knowledge that I have acquired from others through communication and study must be verified and therefore is not necessarily the absolute truth. If someone tells me something new, how can I be sure it is true?

So, as long as I have not experienced this new knowledge – and applied it accordingly – it remains incomplete. There is no doubt that good education is of great value, but until I know how someone has used the acquired knowledge, it is not proven and does not give me the opportunity to benefit from it. Only when it has been tested does it give me an advantage or a certain scope for action and, to some extent, power.

Let’s return to my manager who is open-minded, communicative, strong in leadership and good at solving problems. Couldn’t it be that our potential candidates are managers in the construction, finance or clothing industry? Without their experience, the vacancy would probably have been matched to all three positions, although each job requires its own industry insights. There is a lack of relevant experience to put the skills into a meaningful context.

Real knowledge needs experience

This has been recognized by other job matching experts. The criterion of skills is not sufficient for good matching. If I want to match a job seeker with a certain profession, I cannot only take into account knowledge of the person’s skills based on his/her CV and cover letter. I will also need to know about experience. Only with experience can relationships and industries be developed.

In addition, no one mentions only the skills he/she has – but very often other relevant information that can contribute to a good match. Similarly, in a job advertisement, a company does not specify all the skills it is looking for – and this is a hindrance to matching. Because if a job advertisement appears for a “Data Scientist,” the employer will probably not mention “IT usage” or “data processing” as he/she will assume that such skills are evident from the job title. Similarly, a data scientist would probably indicate in his or her CV more specific skills than those associated with previous job titles. But if that person is to be matched according to skills, then information relevant to this matching parameter will be missing.

If we only matched on the basis of skills, I’m sure we would get different results than if we just compared job titles. However, such an approach is ultimately not good enough to guide people to jobs, applicants to positions and employees to employers. We need more.

Good education does not mean good manners

Knowledge of skills and experience cannot determine whether the new copywriter will fit into the team well, or whether the new nurse will arrive at the hospital on time, or whether the new procurement officer will negotiate well. Who would confide in a CV nowadays that he/she is a poor team player or is unreliable? Yet it is precisely these soft skills and the personality of the applicant that are incredibly important for a good match. A consultant must be punctual for a customer appointment, whereas a programmer can keep flexible working hours. Likewise, the programmer’s appearance is of less importance than that of the consultant. However, if the consultant is unable to speak openly to customers, his company will soon lose them. Accordingly, a match only becomes truly successful if the applicant’s personality is also considered. My CV details a wide range of things I have done, but how I have done them is also crucial.

Pulling together?

Now, if this CV fits that that vacancy perfectly, it is not yet certain that we will have a perfect match. After all, the skills and personality of a new employee have to complement a network of skills and personalities of colleagues. If I’m the only software engineer in a company, I have to be an all-rounder and take the initiative with ease. If I am hired in a team with two others – one of them is more familiar with field X, the other with field Y – skills complement each other and the collaboration creates something completely new. I can ask for help more often and at the same time I am expected to be able to fit in well with the team. The colleagues involved also influence the perfect match. To be precise, the CVs of the staff have to be matched as well.

Whoever still thinks that you can match an employee to a job by taking into account just one parameter (job title, skills, experience or personality) may realize that this can only work well if you are very lucky. If an algorithm is supposed to solve such a complex problem, the chances of a successful match are like those of finding the proverbial needle in the haystack.

So, are we at the end of the road?

Not yet. Confucius made the statement, “Experience is like a lantern in the background; it always illuminates only the piece of road that we already have behind us.”

We have tested our knowledge, brought us and others advantages, we may be punctual and reliable. We are in possession of the required soft skills. This means that we are sure to secure our ongoing business. All deadlines are met, the customers are treated well, and the employees occupy their seats punctually each morning. Everything should be fixed by now.

What truly strengthens a business?

But if everyone always conforms to the requirements, then business remains “only” secured. We don’t create anything new. Creating something new calls for good knowledge and often a great deal of experience. Above all, however, one needs – literally and semantically – creativity.

The Cambridge dictionary defines creativity as “The ability to produce original and unusual ideas, or to make something new or imaginative.”¹ Basically, by going beyond knowledge and experience, creativity gives us a third way of looking at something, which one could call “thinking outside of the box.” As an approach, creativity is therefore less artistic than rule-breaking: radical reworking, thinking outside the box, or throwing the box out altogether. The creative act produces something new, different and maybe a little frightening.

Albert Einstein said that “Creativity is intelligence having fun,”² so a creator is someone who enjoys turning the business around rather than someone who merely meets a catalogue of requirements. Creativity is of the greatest value in times when a great deal of change is happening. After all, anyone who simply adapts during the course of digitalization will not follow, and certainly will not move forward. We need the people who keep an overview. We need the employees who secure the business. And we also need people who show us new ways of doing thing, especially nowadays. Creativity is the most important skill today.

Creativity, intuition, emotions and anything contrary to logical, analytical and rational thinking (which could be considered analogous to knowledge and experience) are often attributed to the right side of the brain. You may have heard the theory that people think more with either the left or right side of the brain. However, researchers have found out that this is a myth. Even if some functions may be attributed more to one side of the brain, results are greatest when both sides of the brain work together in complex networks.³

If I want to create a new product, knowledge of the production processes and the materials required helps me. My experience in planning a new product also helps me. My organizational talent supports the process. But the idea of creating a new product results from my creativity. So, if you are good at something, then you get the best results because all factors are involved at the same time: knowledge, experience, personality and creativity.

Farewell to the notion of the perfect match

Let’s put it in a nutshell: matching cannot be competence-based, skills-based, or based on an ad hoc approach because the problem is too complex. Matching is driven by expectations and expectations change constantly.

Accordingly, there is simply no such thing as a perfect match, because it is impossible to overcome expectations. Expectations are very subjective and can never be fulfilled equally well for all. So we can only evaluate all the factors as far as possible in order to get as close as possible to the perfect match.

The results of today’s culture of matching with data shreds, such as a few skills or cryptic job titles, will destroy the quality of the machine again and again. Matching with data shreds is a tap in the dark. Those who believe that they can match data fragments with arbitrary keywords will never approach the perfect match. As we have mentioned, such an approach ignores other parameters that are crucial for high-quality allocation.

With complex algorithms you can only create the greatest possible approximation if you distance yourself from data fragments and try to include all factors, as does the brain when creating something new: skills, experience, personality and, if treated appropriated, also former job titles. The machine takes all these criteria into account, evaluates them in turn, and gives each a weighting. If these criteria are represented with an adequate weighting, a good starting point will have been reached to bring person and job together using technology. All determinants, including expectations, are aligned and the chances for the perfect match are thereby optimized.

Even with JANZZ. Technology’s well-designed, developed and improved matching processes, it is difficult to consider all factors to the correct extent. Expectations can be mapped on a large scale, but one part is always kept hidden. For example, if unemployed people are to be secured positions, a large part of the expectation is that they will actually be employed. If engineers are to be matched, there is the expectation that the salary band will correspond with that in previous positions. Further expectations can be mapped if it is clear that they exist. Accordingly, we can only approximate the perfect match. However, we are not fumbling in the dark with data fragments. The process may not end with the perfect date – but maybe with an invitation to another one.

Sources:

¹ Cambridge Dictionary (2017). Creativity. Accessed from: http://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/creativity [2017.11.02].

² Einstein, Albert (1930). Mein Weltbild. Wie ich die Welt sehe.

³ Nielsen JA, Zielinski BA, Ferguson MA, Lainhart JE, Anderson JS (2013). An Evaluation of the Left-Brain vs. Right-Brain Hypothesis with Resting State Functional Connectivity Magnetic Resonance Imaging. PLoS ONE8(8): e71275. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0071275

Sahoo, Anadi (2017). Knowledge, Experience & Creativity. Accessed from: https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/knowledge-experience-creativity-dr-anadi-sahoo/ [2017.11.03.].