In recent years there have been many posts, articles and reports on how AI and automation will shape the future of work. Depending on the author’s perspective or agenda, these pieces go one of two ways: either the new technology will destroy jobs and have devastating effects on the labor market, or it will create a better, brighter future for everyone by destroying only the boring jobs and generating better, much more interesting ones. As always, the truth probably lies somewhere between these two extremes. In this post, we want to take a more nuanced view by discussing the most common arguments and claims and comparing them with the facts. But before we get into this, let us first clarify what the AI-driven digital transformation is. In a nutshell, it is all about automation, using AI technology to complete tasks that we do not want humans to perform, or that humans cannot perform. Just as we did in the past, in the first, second and third industrial revolutions.

From stocking looms to AI art

With each of these revolutions came the fear that human workers would be rendered obsolete. So why do we want to automate? Even though in some cases, inventors were, and still are, simply interested in the feat of the invention itself, more often than not an invention or development was driven by business interests. As is widespread adoption. And no matter which era, businesses rarely have other goals than staying competitive and raising profits. 16th century stocking looms were invented to increase productivity and lower costs by substituting human labor. Steam-powered machines in 19th century mills and factories and farm machinery were used for the same reason. Robots in vehicle manufacture in the second half of the 20th century – ditto. Whether the technology is tractors, assembly lines, or spreadsheets, the first-order goal was to substitute human musculature by mechanical power, human handiwork by machine-consistency, and slow and error-prone “humanware” by digital calculation. But so far, even though many jobs were lost to automation, others have been created. Massively increased production called for jobs related to increased distribution. With passenger cars displacing horse-powered travel and equestrian occupations, and increasing private mobility, jobs were instead created in the expanding industry of roadside food and accommodation. Increasing computational power used to replace human tasks in offices also led to entirely new products and the gaming industry. And the rising wealth and population growth accompanying such developments led to increased recreational and consumption demands, boosting these sectors and creating jobs – albeit not as many as one may think, as we will see below. However, we cannot simply assume that the current revolution will follow the same pattern and create more jobs and wealth than it will destroy just because this is what happened in the past. Unlike mechanical technology and basic computing, AI technologies not only have the potential to replace cheap laborers, say, with cleaning or agricultural robots. They have also begun outperforming expensive workers such as pathologists diagnosing cancer and other medical professionals diagnosing and treating patients, and are also touching on creative tasks such as choosing scenes for movie trailers or producing digital art. Of course, we should also not simply assume a dystopian future of less jobs and sinking wealth. But we must keep in mind that currently, in many cases it is more cost effective to replace expensive workers with AI solutions than cheap laborers such as textile workers in Bangladesh.

So, working towards a more differentiated view, let us take a look at the currently most common claims and how they stand up to closer scrutiny.

Claim 1. AI will create more/less jobs than it destroys

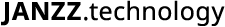

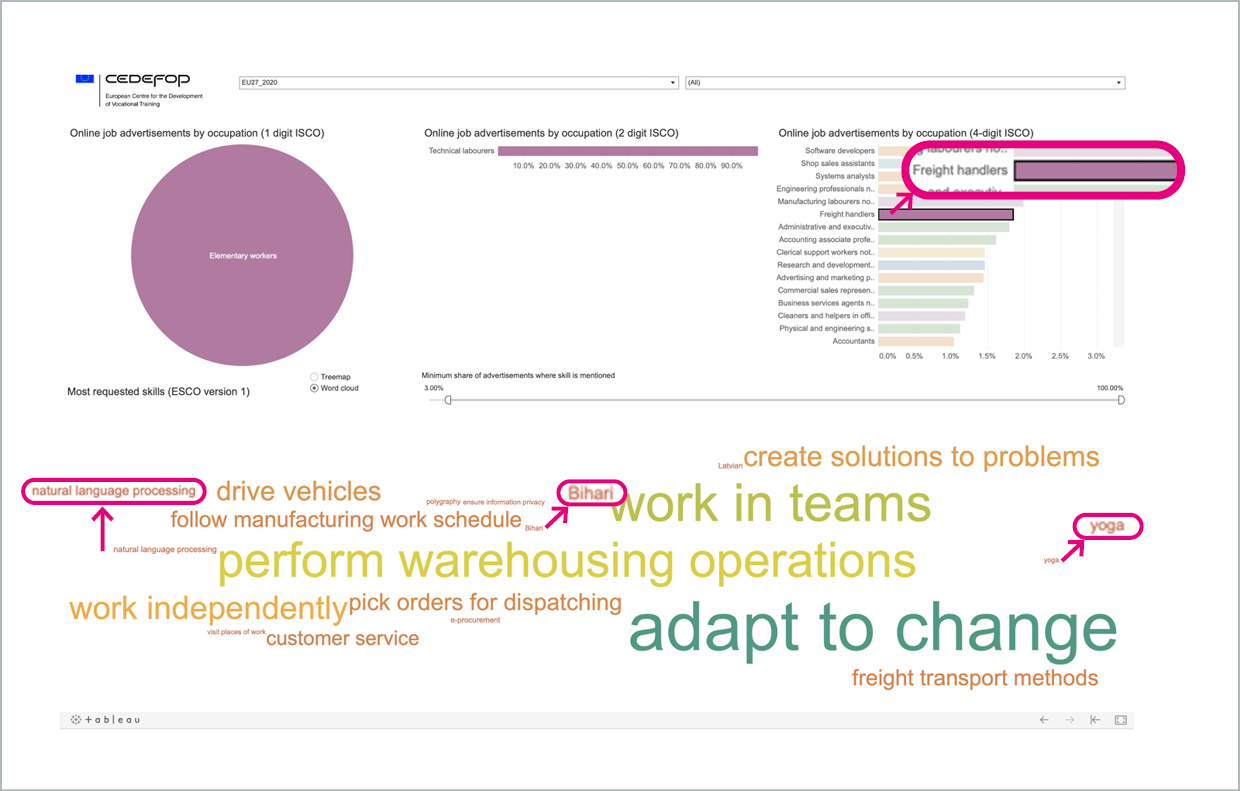

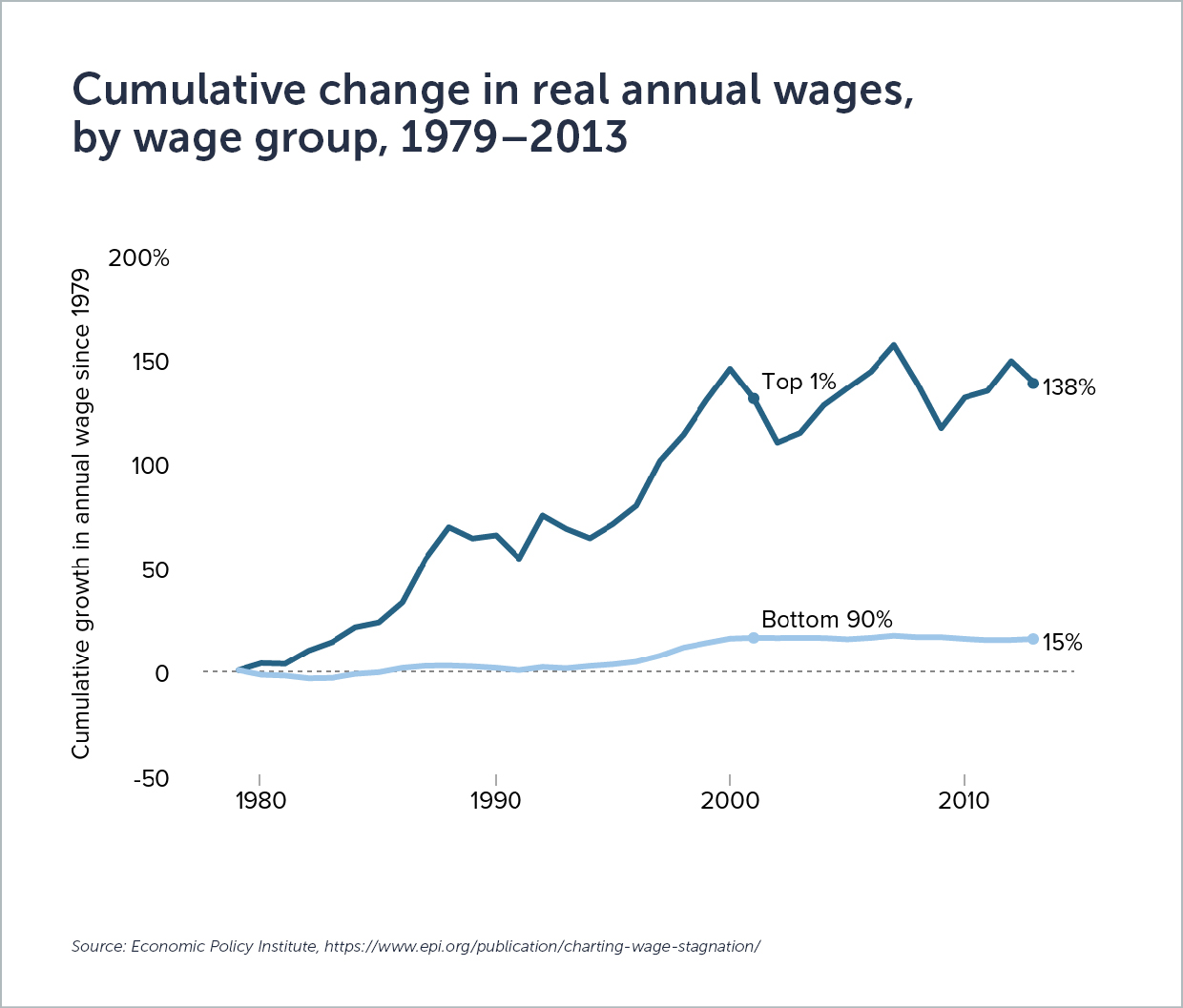

This is the main argument put forth in utopian/dystopian scenarios, including reports by WEF (97m new jobs vs. 85m displaced jobs across 26 countries by 2025), PwC (“any job losses from automation are likely to be broadly offset in the long run by new jobs created”), Forrester (job losses of 29% by 2030 with only 13% job creation to compensate) and many others. Either way, any net change can pose significant challenges. As BCG states in a recent report on the topic, “the net number of jobs lost or gained is an artificially simple metric” to estimate the impact of digitalization. A net change of zero or even an increase of jobs could cause major asymmetries in the labor market with dramatic talent shortages in some industries or occupations and massive worker surplus and unemployment in others. On the other hand, instead of causing unemployment – or at least underemployment, less jobs could also lead to more job sharing and thus shorter work weeks. Then again, although this may sound good in theory, it also raises additional questions: How will pay and benefits be affected? And who reaps the bulk of monetary rewards? Companies? Workers? The government? It is admittedly too soon to see the effects of AI adoption so far regarding overall employment or wages. But past outcomes, i.e., of previous industrial revolutions, do not guarantee similar outcomes in the future. And even those outcomes show that job and wealth growth were not necessarily as glorious as they are often portrayed. The ratio of employment to working age population has remained fairly constant in OECD countries since 1970, rising only from just over 64% to just under 69%.[1] Much of this increase can be attributed to higher labor participation rates, especially of women. And the increased wealth is clearly not evenly distributed, e.g., in the US:

Source: Economic Policy Institute, https://www.epi.org/publication/charting-wage-stagnation/

Source: Economic Policy Institute, https://www.epi.org/publication/charting-wage-stagnation/

There are simply no grounds to assume that AI and automation will automatically make us wealthier as a society or that the increased wealth will be distributed evenly. We should thus be equally prepared for more negative scenarios and discuss how to mitigate the consequences. For instance, would it be acceptable to treat AI processes like human labor? If so, we could consider taxing them to support redistribution of wealth or to finance training or benefits and pensions for displaced workers.

In addition, these estimates should be questioned on a basic level. Who can confidently say that this job will decline? How can we know what kind of jobs there will be in future? None of these projections are truly reliable or objective – they are primarily based on some group of people’s opinions. For instance, the WEF’s Future of Jobs Report, one of the most influential reports on this topic, is based on employer surveys. But it is simply naive to think anyone, let alone a cadre of arbitrary business leaders, can have a confident understanding of which jobs and skills will be required in the future. One should not expect more from this than from fortune telling at a fair. Just take a look at the predictions about cars in the early 19th century, remote shopping in the 1960s, cell phones in the 1980s, or computers since the 1940s. So many tech predictions have been so utterly wrong, why should this change now? And yet, such predictions are a key element in the estimates for the “future of work”.

Fact is, scientifically sound research on this topic is extremely scarce. One of the few papers in this area studied the impact of AI on labor markets in the US from 2007 to 2018. The authors (from MIT, Princeton and Boston University) found that greater AI exposure within businesses is associated with lower hiring rates, i.e., that AI adoption has so far been concentrated on substitution as opposed to augmentation of jobs. The same paper also finds no evidence that the large productivity effects of AI will increase hiring. Some people may be tempted to say that this supports the dystopian view. However, we must also note that this study is based on online vacancy data, and thus the results should be treated with caution, as we explained in detail in one of our other posts. In addition, due to the dynamics of technological innovation and adoption, it is almost impossible to extrapolate and project such findings to make robust predictions for future developments.

And on a more philosophical note, what would it mean for human existence if we worked substantially less? Work is ingrained in our very nature; it is a defining trait.

Claim 2: Computers are good at what we find hard and bad at what we find easy

Hard and easy for who? Luckily, we do not all have the same strengths and weaknesses, so clearly, we do not all find the same tasks “easy” and “hard”. This is just yet another extremely generalizing statement based on completely subjective judgement. And if it were true, then most people would probably consider repetitive tasks as typically easy, or at least easier. This directly contradicts the next claim:

Claim 3: AI will (only) destroy repetitive jobs and will generate more interesting, higher-value ones.

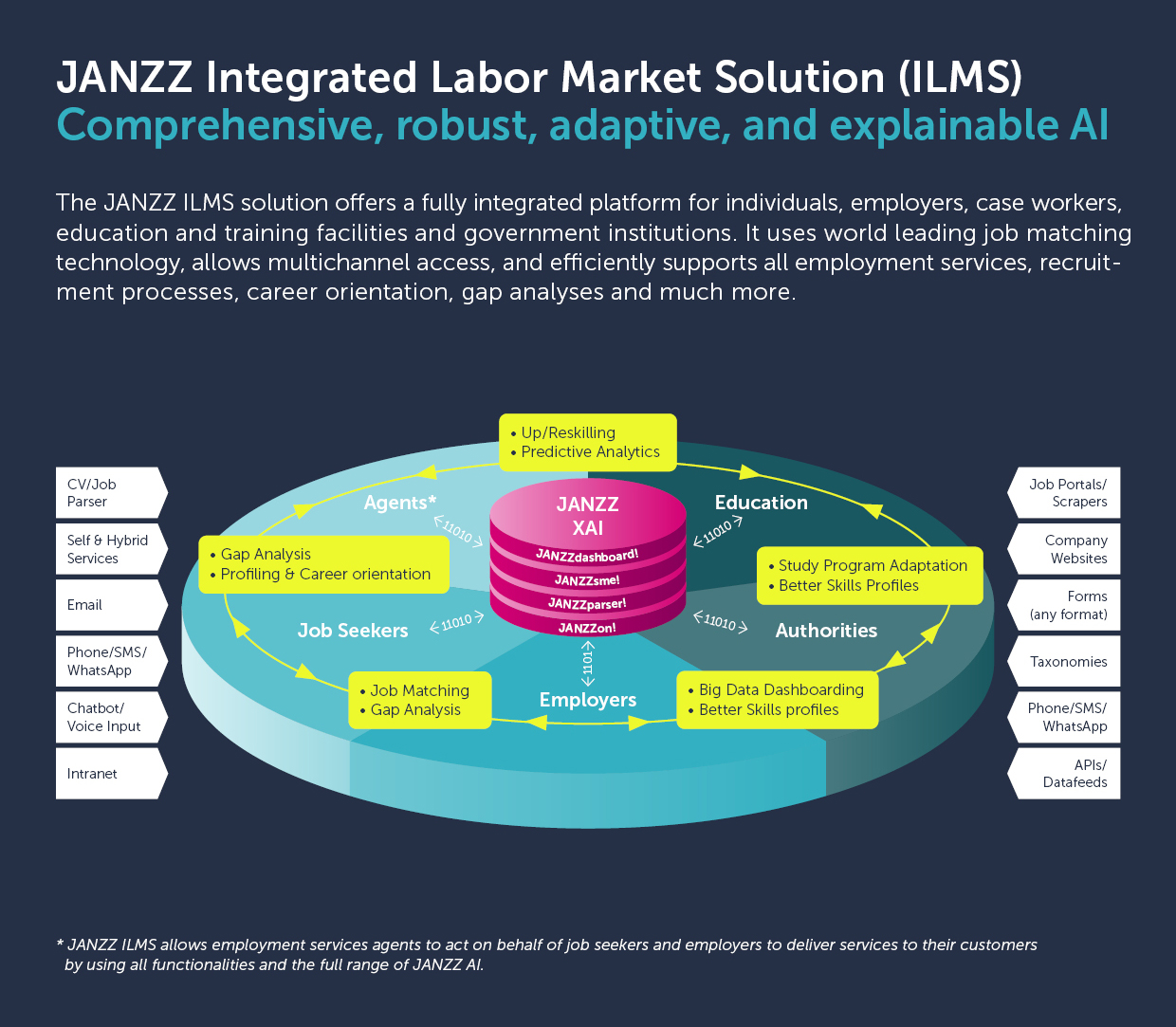

The WEF states that AI will automate repetitive tasks like data entry and assembly line manufacturing, “allowing workers to focus on higher-value and higher-touch tasks” with “benefits for both businesses and individuals who will have more time to be creative, strategic, and entrepreneurial.” BCG talks of the “shift from jobs with repetitive tasks in production lines to those in the programming and maintenance of production technology” and how “the removal of mundane, repetitive tasks in legal, accounting, administrative, and similar professions opens the possibility for employees to take on more strategic roles”. The question is, who exactly benefits from this? Not every worker who is able to perform repetitive tasks has the potential to take on strategic, creative and entrepreneurial roles, or program and maintain production technology. It is simply a fact that not everyone can be trained for every role. More satisfying, interesting tasks for intellectuals (such as the advocates of a brighter future of work thanks to AI) may simply be too challenging for the average blue-collar worker whose job – which may well have been perfectly satisfying to them – has just been automated. And not every white-collar worker can or wants to be an entrepreneur or strategist. Also, what exactly does “higher-value” mean? Who benefits from this? The new jobs created so far, like Amazon warehouse workers, or Uber and Postmates drivers, are not exactly paying decent, secured living wages. And since the early 1970s, businesses have demonstrated a clear disinterest in sharing the added value from productivity gains with workers:

Source: Economic Policy Institute, https://www.epi.org/publication/charting-wage-stagnation/

On the other hand, a vast number of the AI applications that are already available perform higher- to highly-skilled tasks based on data mining, pattern recognition and data analysis: diagnosis and treatment of medical conditions, customer service chatbots, crop optimization and farming strategies, financial or insurance advising, fraud detection, scheduling and routing in logistics and public transport, market research and behavioral analysis, workforce planning, product design, and much more. The full effect of these applications on the job market is not yet clear, but they are certainly not only removing mundane, repetitive tasks from job profiles.

Claim 4: We (just) need to up-/reskill workers.

While we certainly do not disagree with this statement in general, it is often brought up as a more or less simple remedy to prepare for the future AI-driven shifts in the labor market and “embrace the positive societal benefits of AI” (WEF). Fact is, this comes with several caveats which make it a far from simple solution.

First off, we cannot repeat enough that it is not possible to predict the “future of work” reliably, especially which jobs really will be in demand in future and which will not. Also, based on the effects of the previous industrial revolutions and current research, it is highly likely that widespread adoption of AI will introduce new jobs with profiles that we cannot anticipate at the moment. This means we need to equip current and future professionals with the skills necessary for jobs that we currently know nothing about. One often suggested way to work around this issue is to encourage lifelong learning and promote more adaptable and short-term forms of training and education. This is certainly a valid option and clearly on the rise. However, there are several aspects to keep in mind. For instance, 15–20% of the US and EU adult population[2] have low literacy (PIAAC level 1 or below). This means that they have trouble with tasks such as filling out forms or understanding texts about unfamiliar topics. How can these people be trained to succeed at “more complex and rewarding projects” if they cannot read a textbook, navigate a manual or write a simple report? In addition, around 10% of full-time workers in the US and EU are working poor.[3] These people typically have neither the time, resources, nor support from employers for lifelong learning and thus no well-informed access to efficient, targeted and affordable (re)training.

By the time such issues have been addressed, many of these workers may have already missed the boat. In 2018, US employers estimated that more than a quarter of their workforce would need at least three months of training just to keep pace with the necessary skill requirements of their current roles by 2022.[4] Two years later, that share has more than doubled to over 60%, and the numbers are similar across the globe.[5] In addition, even before the post-Great Recession period, only roughly 6 in 10 displaced US workers were re-employed within 12 months in the 2000 to 2006 period.[6] In 2019, this rate was the same in the EU.[7] With increasingly rapid changes in skills demands, combined with lack of time and/or resources for vulnerable groups such as the working poor and workers with low literacy, not to mention lacking safety nets and targeted measures in underfunded workforce development systems, the prospects for these workers are highly unlikely to improve.

Moreover, the pandemic has massively accelerated the adoption of automation and AI in the workplace in many sectors. Robots, machines and AI systems have been deployed to clean floors, take temperatures or food orders, replace employees in dining halls, toll booths or call centers, patrol empty real estate, increase industrial production of hospital supplies and much more within an extremely short period of time. In the past, new technology was deployed gradually, giving employees time to transition into new roles. This time, employers scrambled to replace workers with machines or software due to sudden lockdown or social distancing orders. This is a crucial difference to the preceding industrial revolutions. Many workers have been cut loose with simply not enough time to retrain. Similarly disruptive events may well occur in the future – be it another pandemic or a technological breakthrough – and as a society, we need to be prepared for these events and provide affected workers with swift, efficient and above all realistic support.

Claim 5: Employers should view up- and reskilling as an investment, not as an expense.

If a company replaces all of its cashiers by robots, why would they want to reskill the newly redundant workers? Even governments have a hard time taking this stance on training and education. Many countries focus primarily on college or other education for young workers rather than retraining job seekers or employees. For instance, the US government spends 0.1% of GDP to help workers navigate job transitions, less than half what it spent 30 years ago – despite the fact that skills demand is changing much faster than it did three decades ago. And the vast majority of businesses is primarily interested in maximizing profits – that is just how our economy works. Remember: we live in a world where even sandwich makers and dogwalkers are forced to sign noncompete agreements to prevent them from getting a raise by threatening to move to a competitor for higher pay.

Well-performing conversational software could enable a company to take a 1,000-person call center and run it with 100 people plus chatbots. A bot can respond to 10,000 queries in an hour, far higher than any realistic volume even the most efficient call-center rep could handle. In addition, a chatbot does not fall ill, need time off work, or ask for perks and benefits. They make consistent, evidence-based decisions and do not steal from or defraud their employers. So, if the quality of this software is sufficient and the price is right, there would most probably be an uproar amongst shareholders if a company did not go for this offer. After all, a solution that increases efficiency and productivity while lowering expenses is the ideal of businesses of our time. So, if this company doesn’t opt for it, its competition will. And despite the “tech for social good” propaganda we constantly hear from Silicon Valley, most companies are simply not interested in the future of soon-to-be-ex workers.

Beyond the bubble

The bottom line is that we cannot afford to overdramatize or simply reassure ourselves that there will be enough jobs to go round, or we will constantly be playing catch up. Most of the commonly cited problems or solutions tend to be discussed within the academic or high-income bubble of researchers, tech entrepreneurs and policy makers, mixed with a substantial amount of idealism. But to get ahead of these developments that – for good or for bad – have vast potential to completely transform our labor markets and society, we need to look beyond our bubble and design realistic strategies for the future based on facts and objective data.

[1] https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DatasetCode=LFS_SEXAGE_I_R#

[2] US: https://www.libraryjournal.com/?detailStory=How-Serious-Is-Americas-Literacy-Problem

EU: http://www.eli-net.eu/fileadmin/ELINET/Redaktion/Factsheet-Literacy_in_Europe-A4.pdf

[3] US: https://www.policylink.org/data-in-action/overview-america-working-poor

EU: http://www.europeanrights.eu/public/commenti/BRONZINI13-ef1725en.pdf

[4] The Future of Jobs Report 2018, World Economic Forum, 2018.

[5] The Future of Jobs Report 2020, World Economic Forum, 2020.

[6] Back to Work: United States: Improving the Re-employment Prospects of Displaced Workers, OECD, 2016.

[7] https://skillspanorama.cedefop.europa.eu/en/dashboard/long-term-unemployment-rate?year=2019&country=EU#1