Systematic discrimination against workers age 50+ in candidate selection – or why this is not the issue in the vast majority of cases.

Read on, the following article will not just repeat the same arguments as always on this particularly important topic, which are usually based on assumptions and politically deadlocked positions. We will provide you with new, statistically relevant and number-based arguments that allow you to take a different view on the challenges of older workers and, to the same extent, on our education policy. But let us start at the beginning.

The statistics bring it home…

Suppose we want to fill a new position. We already have 80 suitable applications and CVs, including ones from young professionals, experienced professionals and applicants age 50+. Let the selection process begin. We sort by relevant skills and competences, professional experience, education and training, language skills, specializations, industry knowledge and so on. We reduce first to five, then to three candidates, who we invite to an interview. Importantly, we hide all personal data during selection, or rather, we make a non-discriminatory first selection using XAI.

At the end of this not so fictitious example and after many long, personal interviews and assessments, we choose a 27-year-old, multilingual university graduate with almost three years of experience in the right industry and the best matching scores in the areas of hard skills/competences and soft skills, communication skills, appearance, etc. A surprising choice? Hardly. It is rather the logical result of a structured, transparent and above all fair selection procedure. Remember, the hiring HR professionals were not aware of age, gender or salary expectations for the first steps of the selection. It would have been more of a surprise if one of the 50+ candidates had won the race – for statistical reasons alone: in the total of 80 applications there were only seven more or less suitable 50+ candidates, i.e., less than 10%.

Imagine that a 54-year-old, less qualified candidate had been chosen, contrary to the robust findings of the structured selection process and results of the interviews, primarily because of his age. This would have been just as discriminatory as an inherent preference of male candidates or favoring the candidate with the necessary connections.

Let us explain in more detail why this choice is logical and fair, and why other, similar selection processes usually have just as little to do with age discrimination or with the argument that companies avoid recruiting 50+ candidates for financial reasons.

There are always better qualified candidates out there. No matter how good yours are.

Well-trained, enthusiastic and experienced engineer, 50 plus, seeking – this is a scenario that has become bitter reality for many older workers in recent years. In our example, by the way, six of the 80 applicants were ahead of the 50+ candidate, having even better qualifications, mostly just recently acquired or refreshed, and higher degrees. There was only one criterion, ‘relevant experience’, on which he came in fourth, just narrowly missing the interviews for the final selection round. In short, the candidate was not unsuitable or rejected just because he was over 50, there were simply better-suited and objectively better qualified candidates for the position.

By the way, according to some of the more serious statistics, jobseekers in many industries in Switzerland already start facing more difficulties when they reach their mid-40s. At this age, the chances of finding a suitable job fall significantly in more and more cases. Despite an exceedingly positive economic environment and stable labor market with an exceptionally low unemployment rate before Covid-19, even highly qualified older workers were concerned about potential, longer-lasting unemployment. The fact is that once the older generation have lost their job, it is difficult for them to find a new, equivalent position. This is primarily because, usually for the first time in many years, they will have to face up to the ever increasing, ever better educated, multilingual competition and keep pace with younger, highly motivated and equally ambitious applicants.

To be very clear at this point: The sad exceptions do exist, companies with a real prevailing ‘anti-50+ policy’. Such a policy makes no sense at all, economically or otherwise, but there have always been companies that could neither calculate nor had a reasonable and fair personnel strategy. However, the real reasons why people in their 50s are increasingly faced with unemployment are complex and found on both the employer and employee side.

Last relevant vocational training: commercial apprenticeship 1981

The current labor market is becoming more and more specialized and is exposed to ever-faster technological change in many sectors, not only because of advancing digitalization. There are several reliable surveys that consistently show that, by the age of 30, more than 60% of knowledge acquired up to that point is already outdated or no longer relevant for professional progress.

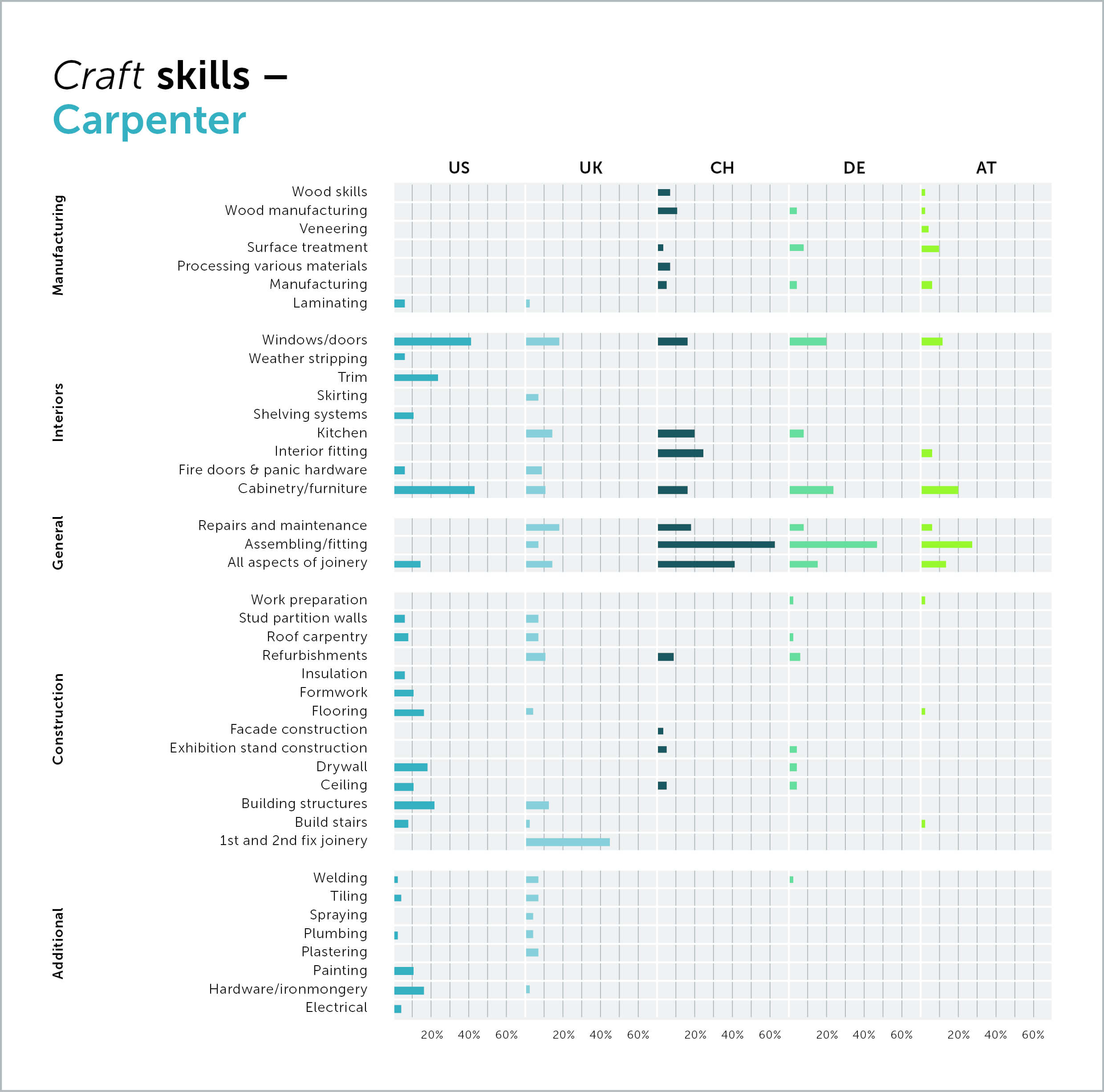

In recent years, digital technologies, channels and thus evolved processes have come to the fore, rendering tasks more demanding and complex, especially for older workers. For example, compare the top 20 required skills from 2008 and 2018, say, on LinkedIn or in similar surveys. The ongoing transformations and the digitalization of competitive skills are quite dramatic.

This is just one of the reasons why training is being invested in everywhere and more than ever. That is a good thing, we all fought for this privilege for a long time and have repeatedly stressed the importance of good, modern education for every economy. Access to education as affordable as possible for all. A whole variety of tailormade educational models, dual education, vocational baccalaureate, semester abroad, MBA, CAS and much more. Comparing the manifold possibilities of today’s educational landscape, not only in Switzerland, with the options that were available at the time of our 50-year-old engineer, there have been huge, mostly positive developments – consistently and in all areas and aspects that are key to a successful professional life. Moreover, ambitious young professionals will gladly pay, or rather invest, 60000 US dollars and a few months of their lives for an MBA or tens of thousands of francs for challenging advanced training, certifications or postgraduate studies in order to have a better chance in the competition, which is becoming tougher for younger workers as well. We must all be continuously willing to make such investments, including the time commitment and renunciation of family life and leisure time ensued. Lifelong learning and continuous training are more than just buzzwords.

To keep up with a constantly evolving labor market, it is absolutely necessary to continuously train and extend our skills and competences, on average every 5 to 7 years. Work experience is certainly valuable, but that value is diminishing in more and more areas because the businesses they are based on are often outdated after a few years or have disappeared completely from the market. The ever-accelerating cycles of innovation in basic processes, tools and market and production mechanisms render the by far largest asset of experienced workers increasingly obsolete in comparison with younger, often better trained co-applicants.

The problem for the 50+ generation is that their good education was completed many years ago. Their knowledge, should they need to transition from a familiar and well-known environment to a new field of work, is thus no longer up to date.

Also, many 50+ applicants list only a few, if any, current training courses on their CV. For instance, a TOEFL test from 1993 may be the last entry under ‘languages and communication’, hidden among an abundance of in-house courses and trainings with lavish certificates of little meaning or relevance to a new position. This can be confirmed statistically by parsing and carefully evaluating large quantities (several million) of anonymized CVs: on average, the last relevant qualified formal training was completed 11.2 years earlier for 50+ candidates in Switzerland. In cases of successful professional reorientation or re-entry into a profession, it was several years less. As a reminder, the iPhone as the first actual ‘smart phone’ was launched almost exactly 11 years ago. Several other, significant digital processes and tools have followed since – at ever-shorter intervals.

In such cases, companies cannot be blamed for not considering a 50+ applicant for the simple reason that younger applicants are statistically in the majority and are moreover better qualified or have more up-to-date competency profiles. It would therefore be particularly important for older jobseekers to continuously adapt their strengths and qualities to technological change (whether we like it, want it or not…) and to consider continuous, targeted further training or even reorientation. Self-commitment is called for and this is not the responsibility of employers.

Know-how and relevant competence profiles beat experience.

Another reason why older applicants’ dossiers often end up on the rejection pile is the number of years of service. Applicants who have worked in the same department, company and industry for 20 years have specific work experience but often lose touch with the rapidly changing professional world outside the company. However, this long-term, one-dimensional experience is not the main obstacle in itself: it is often more likely the fact that the applicants’ profile is strongly tailored to their former employer and their qualifications are too limited or they are too specialized, having spent many years in the same function with similar tasks. As a result, flexibility and new professional opportunities are often deemed difficult. A new employer would need to invest in thorough onboarding and possibly in retraining. Of course, this may be necessary for a younger applicant as well. However, it may greatly devalue the importance of acquired professional experience in the competition with other candidates. Even if relevant work experience is still very important in general, its importance has diminished in a fast-moving and even faster changing economy. Ten years of experience are no longer twice as good and meaningful as five. Or rather, only if the competence profile has been developed in parallel with experience gained and according to the latest requirements. Unfortunately, this is exceedingly rare, as the data from the many parsed CVs clearly show.

Protect a lack of qualifications?

Lately, there have been repeated discussions about special protection against termination or special quotas for over 50s, in the hope that this constantly growing problem will be mitigated in the long term. But are these ideas not extremely unfair and discriminatory towards younger and usually better qualified workers? Workers who are already severely disadvantaged when it comes to major topics such as retirement provision, and thus are already proving more than enough solidarity with older workers.

Such an approach leads to unacceptable discrimination against younger generations by protecting less-qualified applicants. Not only that, such a rule would also mean that current 50+ jobseekers may no longer be recruited because employers fear that they will not be able to dismiss them. This type of reaction can be widely observed in countries with rigid employee protection laws such as Germany and France, where, as a result, many employers strongly favor fixed-term over permanent contracts. Special protection against termination is thus not a solution, it is a fallacy.

Another idea aimed primarily at mitigating the consequences of systematic age discrimination is the bridging pension (rente-pont). But if that is not the driving factor behind long-term unemployment of older workers, then this will just amount to yet another instance of discrimination against younger jobseekers. Instead, older jobseekers should be trained – many of them barely know how to apply for an opening. Looking at their CVs, you immediately encounter the showcase syndrome: instead of listing relevant skills, the document is adorned with information of no relevance whatsoever such as obsolete programming languages learnt 20 years ago. As a consequence, such an applicant will often seem desperate and insecure, not like a proud, promising new employee who will support the department and enhance it.

So why hire over 50s at all?

Too expensive, too little professional expertise, too inflexible – these are classic stereotypes older employees are branded with. True, the younger generation is usually more flexible and mobile in terms of time and place of work. Sell my beloved house after twenty years and move far away to another city or canton? No thanks. The reality that wages automatically rise with increasing work experience and age is another fact that is never questioned and rarely discussed publicly. And yet, this is another point where performance should be assessed rather than age. Why not earn the most when we are at our most performant and our expertise is its most comprehensive and up to date?

And finally, young jobseekers often also boast more extensive language skills and are, for the most part, much more IT-savvy. However, a few arguments speak in favor of the older generation: they have a high sense of duty and responsibility, very often have a positive attitude to work and are usually regarded as balanced and notably more consistent.

Anyone who now thinks that these issues can be reduced with anonymized AI-based application procedures is completely wrong unfortunately. These procedures do not focus on the person, but on relevant skills, current education and training, language skills, industry knowledge and specializations. An evaluation of various applicant selection processes in a wide range of occupational groups and industries has shown that, in fact, (with the exception of select management positions) the pool for the next round usually contains a significantly smaller proportion of 50+ candidates than in conventional selection procedures. This in turn proves that it cannot be due to the age of the candidates because all personal characteristics such as age, gender, origin, etc., were fully disregarded in the selection process and thus played absolutely no role in the matching and ranking, which formed the basis for the interview invitations.

We must therefore find other strategies. The key is ‘to be found’ instead of ‘to search’. Positions tailored to over 50s are often not found in job postings. However, there are technological tools that ignore these common prejudices against older employees. Machines decide on the basis of matching data points. They do not know discrimination against age, gender, ethnicity, etc. Older applicants should utilize this opportunity, especially to find out what they can draw on to increase their chances. These tools also give very objective and sober answers to many questions such as how many matches do I really get with my current qualifications? Where are my personal skill gaps? In the mind of the machine, there is no ‘I didn’t get the job, wasn’t even shortlisted just because I’m over 50. Sure, that figures…’

Using these tools, employment services, recruiting companies, job portals and others can make attractive employment proposals to 50+ talents, but also pinpoint individual placement challenges. For a gap analysis, feel free to ask for help at info@janzz.technology