Standard skill profiles – chasing white rabbits and other myths

Many employers struggle to articulate and communicate the skills they value most for a given position and this results in a myriad of variations in the vocabulary used for job postings. Today, with the possibilities opened up by (X)AI automation for recruiting processes, many globally positioned recruiting agencies or HR divisions are tempted to ask if AI could provide a quick fix to these struggles, say, by generating a one-size-fits-all skill profile for a given profession. The lack of a common vocabulary among stakeholders in the labor market is of course a hindrance: many job portals are based on keyword matching, which leads to missed opportunities for both jobseekers and recruiters due to differing vocabulary, and AI-based automation struggles with the wording of job postings written to attract talent. This issue can indeed be addressed by employing semantic technologies, which, in a sense, translate the many linguistic variations into a common vocabulary, significantly improving job-candidate matching. However, although such technology can generate standardized vocabulary, this does not mean that it can generate a standard skill profile for job postings. The pertinent question is, does such a global skill profile even exist? Is there enough common ground in job postings around the globe for a given profession to define such a skill set? Or even in single countries?

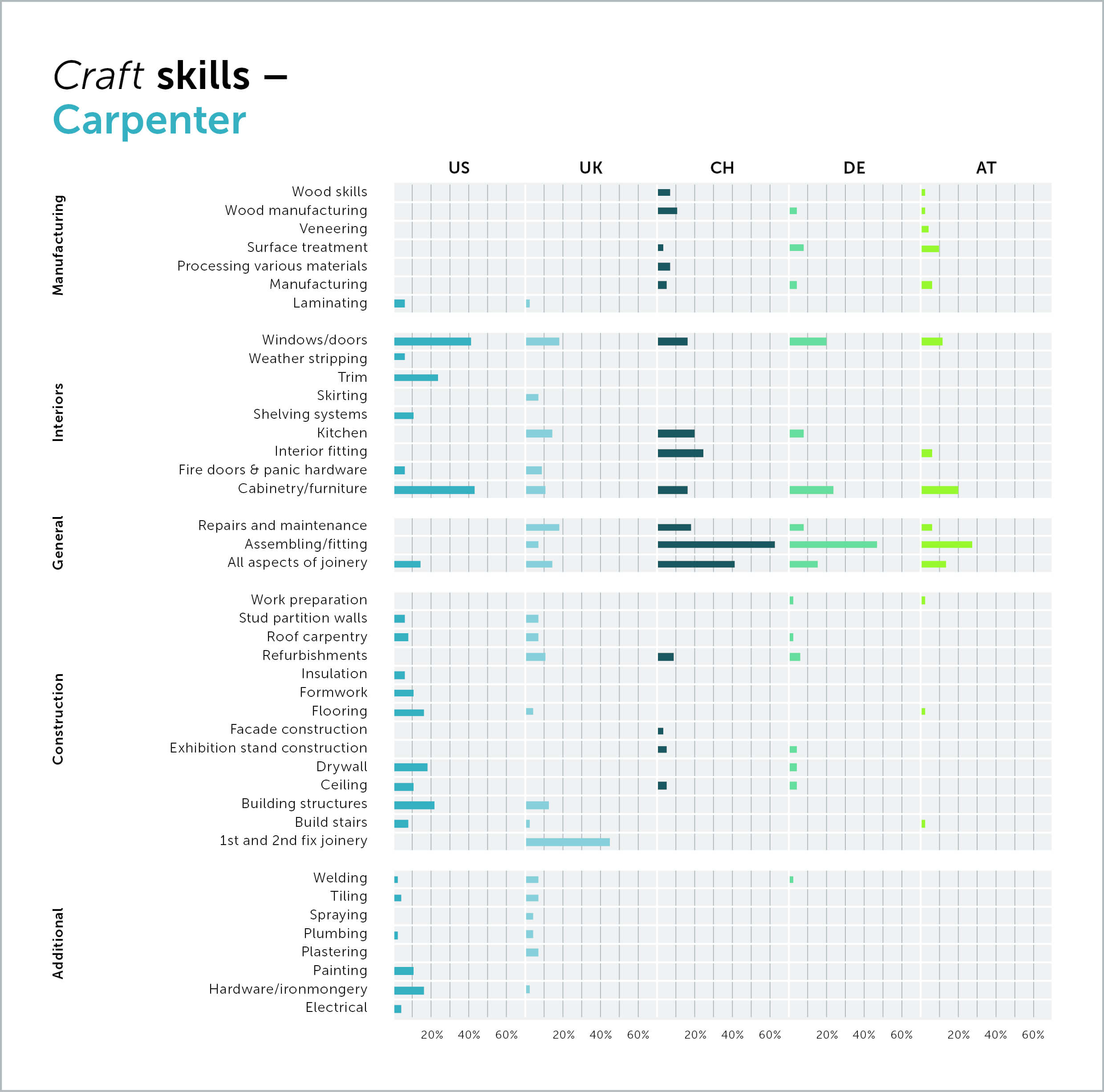

JANZZ has analyzed millions of job postings over the years to investigate these questions. To illustrate our findings, let us explore skill profiles for two classical professions, carpenter and nurse. We randomly selected around 250 job postings for each of these professions from five countries in two language regions: United States, United Kingdom, Switzerland, Germany and Austria. Our evaluation shows that there is a vast amount of variation in skills required for individual positions, even in strongly regulated professions such as nurse.

Skills may define jobs. But who defines the skills? A business in one country may not be looking for the same person as a comparable business in another country because the skills depend not only on the specific work to be done, they also depend on cultural or regulatory factors, the educational system and many other aspects. In fact, in one country several people with distinct skills sets may be required to do a job that, in another country, just a single person may already be qualified to do. Strong variations in skill profiles can be observed even within the same region because different businesses position themselves differently in the market. This can be seen not only in the varying demand concerning professional skills, but also in required soft skills, which can reflect a company’s philosophy, team dynamics or client expectations.

Impact of education and work experience

Let us take a closer look at carpentry. Germany, Austria and Switzerland (DACH) have a dual education system, where students can train as apprentices in one of a given list of occupations, including carpentry. The precise (hard) skills and theory taught are strictly regulated and defined by national standards, including those for several specialties that can be chosen after basic training. Anyone seeking to train as a carpenter has little choice but to take this path in these countries. The United Kingdom has recently implemented a fully revised apprenticeship structure with national standards for a growing number of occupations and is developing incentives for employers to hire apprentices. However, even though apprenticeships exist for certain occupations, for any one of these there is an alternative route via college education, which is just as (if not at least as) widely accepted. In addition, as these structures are still very new, the majority of the workforce in such professions did not complete an apprenticeship.

The United States are at the other end of the spectrum in this regard. Apprenticeships do exist, but there is no single set of standards that all employers in the US must follow when designing their apprentice programs. This makes it difficult for employers to assess the training of a prospective employee and may be one of the reasons – apart from a lack of tradition for this type of training – why apprenticeships are still not nearly as widespread as in Europe. This is reflected in the numbers of apprentices per capita: in the UK, Germany and Austria around 2% of the working age population are currently in apprenticeship, and just under 4% in Switzerland – more than ten times the number for the US, which is less than 0.3%.1) So, what does this have to do with a skill profile for job postings? One aspect we observe is that in countries with standardized training, much more emphasis is placed on vocational education compared to work experience. This can be seen by taking a simple count of these criteria as required in job postings.

Education and experience – Carpenter

Outer ring: percentage of carpenter job postings requiring given criteria.

Inner ring: percentage of job postings listing at least one criterion in experience and in education.

Center: the number at the center of the chart is the ratio of required experience to required education. A number above one thus indicates more demand for experience than education, and vice versa for a number below one.

To state the obvious, if you have completed an apprenticeship, you also have work experience. And if very few workers have done an apprenticeship, then employers will ask for work experience instead. This is also confirmed by our data for nurses. This profession is highly regulated in all five countries, requiring training (practical and theory) according to predefined national standards, and with specific optional specialties. In all five countries, there is significantly less demand for work experience compared to education (see Fig. below). We also see that in postings for carpenters, experience in tools is much more often explicitly mentioned in the US. This may also be a result of the lack in standardized training, where experience in tools is a given.

Education and experience – Nurse

Outer ring: percentage of nurse job postings requiring given criteria.

Inner ring: percentage of job postings listing at least one criterion in experience and in education.

Center: the number at the center of the chart is the ratio of required experience to required education. A number above one thus indicates more demand for experience than education, and vice versa for a number below one.

Turning to craft skills for carpenters, i.e., hard skills directly related to the trade, we see marked differences in all categories. In the UK and US, demanded skills are scattered across all areas of carpentry, from general over construction and interiors to additional skills from other trades, whereas in DACH, the focus is clearly on general aspects of carpentry with little mention of specific skills. A fully trained carpenter is typically more diversely skilled than one who learnt on the job and thus employable for a wider variety of tasks, which do not need to be explicitly mentioned. By contrast, in countries with less standardized training, carpenters are often restricted to fewer, specific tasks within a job. Notably, apart from laminating, there is no demand for manufacturing skills in the US or UK in our data. This type of knowledge is highly specific to skilled carpentry and requisite in one in five DACH postings. On the other hand, we see some demand for skills from other trades in the US and UK, which is (almost) inexistent in DACH. This is not surprising if we consider that a trained carpenter is less likely to have learnt skills from other trades, whereas a worker who learnt on the job may have acquired any number of other such skills.

A similar effect can be seen for nurses: there is generally little mention of professional skills in all five countries, and particularly few offers detailing specific skills, ranging from 4 to 10 percent of job postings per country. The focus in this skill category is primarily on specialties and additional tasks, which are not part of standard training and/or experience.

Regional differences

There are also other factors that influence the skill profile. For instance, in the UK, soft skills appear to be of little importance in carpentry: less than half of job postings in the UK ask for any soft skills at all, compared to 76% in the US and around 90% in DACH. In the US, the top 3 demanded soft skills are physical fitness, flexibility and overtime, and teamwork (in this order). By contrast, the top 3 skills in DACH are teamwork, working without supervision, and reliability. This shows that employers in the US are typically looking for very different workers than those in DACH.

Interestingly, there are also significant differences regarding soft skills for nurses: in DACH, every single job posting demands at least one soft skill, with a median of five, whereas in the US and UK, only 70 and 80 percent of job postings ask for soft skills, with a respective median of one (US) and three (UK). The top 3 skills in Switzerland are teamwork (48%), responsibility (46%) and working without supervision (44%). In the UK, the top 3 are communication skills, a caring personality and motivation – but with much lower demand (40%, 26% and 26%, respectively). Again, we see very different criteria in different countries.

Another aspect to consider is regulatory matters and safety standards. In the US and UK, employers explicitly ask for knowledge of safety standards (OHSA and HSE/CSCS card) and a significant percentage expect employers to have their own tools. This is not seen at all in DACH and can be traced back to educational and regulatory differences. Similarly, three in four US job postings specifically ask for BLS or similar certifications for nurses, which are part of standard training in the other four countries and thus not mentioned.

Business/industry-specific differences

Suppose we still want to create a standard skill profile. The simplest strategy would be to include any criteria found in at least one job posting. Using our data for carpenters, this would result in a list of 103 requirements, most of which would be completely irrelevant to an individual opening: on average, seven skills are listed per posting, with individual numbers ranging from 2 to 21. For nurses, we would have 94 requirements, with an average of eight skills per posting and a range of 1 to 16.

Another strategy one may consider is to search for a common denominator, for instance, all skills required by at least 25% of job postings in each country. Taking another look at the data above, this leaves us with just two criteria for carpenters: work experience (of unspecified length) and a driving license. Most recruiters would find this unacceptable. In Switzerland, a completed apprenticeship is a must in a vast majority of job postings, whereas in most cases in Germany a driving license is not a requirement. Thus, such a profile would result in many unsuitable candidates in one country and in too few candidates and many missed opportunities in another.

Following this strategy for nurses again yields just two criteria: nursing certification and work experience (in any specialty). Not one soft skill is listed although there is a strong emphasis on this category, with at least 70% of job postings ask for such skills. Moreover, three in four job postings in Germany do not require work experience. Again, this would result in a significant mismatch of candidates to job openings.

Let us pursue the 25% strategy for a single country, say Switzerland. Our standard skill profile for nurses reads as follows:

- nursing certification

- work experience

- care work

- computer skills

- responsible

- stress-resistant

- communication skills

- empathy

- social competence

- teamwork

- professional competence

- flexibility and overtime

- ability to work without supervision

At first glance, this seems acceptable. However, almost 70% of Swiss job postings ask for professional skills other than generic care work, with more than half demanding specialty knowledge not included in basic nurse training. This means that each individual job posting now needs to be fine-tuned according to the specific opening.

For carpenters in the US we also encounter such issues. Our strategy generates the following skill profile:

- work experience

- experience in tools

- cabinetry and furniture

- window and doors

- teamwork

- flexibility and overtime

- physical fitness

- ability to follow plans

- math skills

- knowledge of safety practices

- driving license

As before, this seems adequate at first. However, focusing on craft skills, a worker skilled in cabinetry and furniture or windows and doors may not be experienced in drywalls, roof carpentry or other building structures as this requires a different skill set. Also, a full 80% of job postings require craft skills other than those listed in our profile, and 60% of job postings ask for other soft skills.

Similarly, the only craft skill listed in a thus standardized skill profile for Austria would be assembly and fitting. Yet, many carpentry jobs do not involve assembly and fitting at all, such as seven in ten of the job postings in Austria that require manufacturing skills. In this country, manufacturing techniques are learnt in an apprenticeship with a different specialization and thus, an average assembler/fitter will not have the necessary skills.

Back to square one

These are arguably basic strategies, and a sophisticated AI-based method may deliver slightly better results. Yet the key issue identified in our analysis remains unresolved: there is an immense amount of variation attributable to national and regional differences, and also resulting from differing requirements for positions across different industries and even within individual businesses. Our data show that any globally defined core profile must therefore be adapted to the country (e.g., to accommodate educational, regulatory and cultural factors), then to the industry (construction, manufacturing, etc.), to the individual business (e.g., company culture), and finally, to the individual position. Which brings us back to individual job postings. Thus, a standard skill profile simply does not exist.

1) Own calculations based on figures from OECD and national statistics offices